Drawing on a large-scale comparative study of scholars in the UK and Germany on how pressure to publish is experienced across research careers, I argue that the structural incentive to publish inherent to research assessment in the UK shapes a research culture focused on output and monologue at the expense of an engaged public dialogue.

Published in: LSE Impact of the Social Sciences, 2023.

Governance by output reduces humanities scholarship to monologues

The humanities are often said to be in crisis. The reason given is that they are no longer of use in contemporary society, or that humanities scholars are too concerned with themselves and their niche scholarship. In short: you cannot buy anything with humanities knowledge, and it does not foster innovation and growth in the way science does. A notable defence claims that the humanities are not for profit. They are valuable for democratic society precisely because they are no tool for growth, but for reminding us—as a democracy and a society—for what we are and how we arrived at this state.

Scholarly discourse and publications mirror this. Scientists publish knowledges that are independently useful to society. They foster innovation and growth by providing new explanations of nature or technologies. Because of this reduction to output, scientific discourse itself seems to depend on novelty much more than on its history. You only need the news to make a profit on science. There is no such news in the humanities. You cannot take away a novel humanities text and make a profit on it. In fact, most texts alone are of little use generally. Discourse in the humanities is intricately dependent on the dialogue itself. Each new text is of little value without its history and textual tradition. As a result, understanding the dialogue itself is the knowledge. In other words, the history of discourse is as important as is its differentiation.

Humanities Authorship: The Reduction of Scholarship to Output

Good governance of the humanities as an institution means fostering this. It nurtures dialogue instead of output. In the UK, the Research Excellence Framework (REF), through its focus on research outputs, implements the opposite. It fosters what is commonly known as publish or perish, a narrative construction that underpins the logic that traditional publications are the key to a life in the academy. This pressures scholars to work towards more output at the price of disengaging in dialogue. In a large comparative study of more than 1,000 scholars in Germany and the UK, I looked into the prevalence and underlying motivations of this pressure.

As an example: in both Germany and the UK, the experienced pressure to publish is high among early-career scholars. This is true for both journal articles and monographs. It is even higher at the outset of a career in Germany. This is due to the tremendously conservative career system in Germany, which is still governed by the idea of the traditional professorship. Only few will eventually continue to this secure, long-term position. However, among the few who achieve this (usually after 10-15 years in academia), the pressure to publish decreases significantly, especially for monographs. This is different in the UK, where the pressure stays high for monographs and even increases in terms of journal articles. Nearly 80% of UK humanities scholars in the range of 16-20 years in academia claim to experience (high) pressure to publish articles, with only less than 50% of German scholars at the career stage.

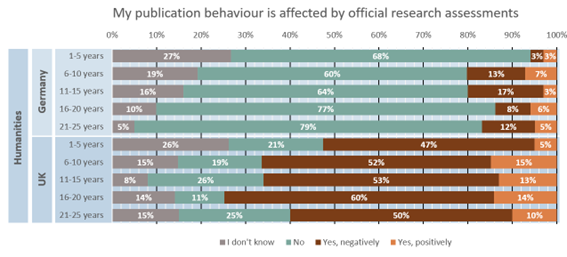

The underlying connections are significant. The pressure to publish is high among early-career scholars in Germany, but this is a structural issue of grounding a career. In the UK, pressure is seen as strongly connected to research assessments, such as the REF (or similar mock exercises leading up to the REF). The striking feature of this is that it affects not only early-career scholars but senior scholars. Even after twenty-five years in academia, half of all UK scholars in the humanities experience a negative impact.

Figure 1: Publication behaviour affected by official research assessments (such as the REF or the Exzellenzinitiative); from Authorship and Publishing in the Humanities, p.104.

There is more detail to this finding, and it is not universally applicable. It is also by no means to be understood as an apology for the German career system which has tremendous problems of its own (Bahr et al., 2022). But, the constant focus on more output by being held accountable on quotable, measurable impact through definite productivity pushes the meaning of publish or perish from an early-career issue to a career-defining one that ultimately shapes scholarship.

In the UK, a scholar remains confronted with the pressure to produce output—not only to define the foundations of their careers, but to fulfil unwritten quotas or satisfy structural demands and their department’s REF guidelines. Indeed, the publish or perish narrative mediates intellectual work across the spectrum of career positions. Irrespective of position, scholars face the pressure to produce new material, to do so in a concrete timeframe, and to publish in established ways.

Of course, its supporters would argue, the REF is neither about quantity of output, nor does it detach publications from their context. In the end, it is managed by peer review. But, the problem goes beyond the guidelines of the REF itself. The REF is only the most prominent manifestation of publish or perish (in the humanities). We only need to look at the job market, where the talk of being REFable—of having enough output for the next mock REF exercise—becomes a defining feature. Like the stars it awards: what the REF means in everyday academic life is more important than what it says to mean on paper.

Publishing in the Humanities: Competition for Output instead of Rational Discourse

To outsiders, the REF appears to be a means for the distribution of funding. But its rating mechanism—a means of distributing symbolic reward—has surpassed its end of distributing funding. Universities compete for artificial excellence to gain a reputation advantage in the form of stars. The more stars a university has, the more attractive it appears. This consequentially turns individual scholarly output into a means to make a profit. The humanities bear a considerable portion of the costs of this marketing strategy. Against their nature, they have to perform for profit.

This essentially turns the idea of the humanities being not for profit against themselves. Constant concern with output reduces the ability to engage with others. Instead of listening to the arguments of others, educating better teachers, or working on an intellectual ability, scholars rush towards publishing apparently novel works (and doing so in traditional, closed ways instead of more progressively: open access; there is still no open humanities on par with open science). This performance for profit reduces dialogue for the sake of monologues, which ultimately is to the detriment of wider society. Here, again, scholarly discourse might be seen as a mirror. The principles of rational discourse are essential—to both democracy and the university. They require not always pushing your own voice, but actually listening to others and engaging with their arguments. The REF’s drive for artificial excellence enforces the opposite. It is the price of managing individual excellence that comes at the cost of losing structural quality.